OFFER: A BRAND NEW SERIES AND 2 FREEBIES FOR YOU!

Grab my new series, "Love and Secrets of the Ton", and get 2 FREE novels as a gift! Have a look here!

Chapter 1

Although aware of her own beauty in the mirror, Vera Ladislaw was not terribly au fait with its effect on men. It was a new power that was only just dawning on her, and she found herself intrigued by its effects.

She had in the last year or so of her flowering become aware of their oddly sweaty brows or, at times, unpleasantly leering smiles. On other occasions they seemed over-gentle in their desire to serve her tea or help her into a carriage, even when, by any estimation of blood, they were of far superior stock than her.

She had not yet decided if she found these attentions flattering, which of course they were, or frightening as she found herself increasingly studied as if she were one of her father’s specimen butterflies pinned under a glass.

To be a foreign aristocrat was a great leveller in England since so many of such diverse ranks had slipped across the Channel chased by the Corsican devil, Napoleon, in the preceding years of conquest.

The Ladislaws had established themselves before this fashionable rush, having come across from Poland in the ’70s when Prussian upstarts had replaced the Polish aristocracy at sword and musket point.

The Ladislaws had been established in and around Bathcombe for long enough now to have all but lost their accents and to have established a thoroughly, in their view, debased living as merchant farmers.

Great-grandmother Ladislaw had been forced to pawn the family’s State Tiara to provide capital for her husband’s business, and although they now lived on a small country estate owned outright – and were able to keep Mishka, their maidservant – the need to work for a living still stung for Vera’s Maman and Papa.

One thing about her beauty that Vera had become used to was the knowledge that in the mind of Maman and Papa it was hitched firmly to the family’s For several months, the farm had been assailed by suitors invited to view her rather in the way Papa would take prize cattle into the market, and with each visit Maman had repeated the importance of a suitable match, through which the family might come by a title in their new country.

A poor choice on the other hand, in the overwrought words of Maman, would condemn the family ‘to join the growing bourgeoisie of industrial England.’

So Vera had spent many an afternoon over the summer at tea and cakes with men of many professions, so long as that profession yielded at least eight-hundred a year, or else came with a peerage.

Vera took the task of understanding these men very seriously but found almost at once that it was impossible to draw a man into a discussion. She was either mumbled at by the weak, or ignored wholly by the strong that saw her as little more than a clothes-rack or doll.

Today, however, the suitor in question had made a promising start. He was young, showing signs of much the same lack of surety that Vera herself felt. A man with a regimental uniform and the beginnings of what was clearly his first moustache growing unconvincingly from his upper lip.

He sipped his tea and a rime of milky brown hung in droplets from the sparse down of his upper lip. Vera was distracted enough by the mishap that she almost missed his proud boast to be heading to, ‘Your homeland, Poland, I hope. We are to be sent to reinforce the Prussians against Napoleon’s advance.’

‘I am sure you are aware that the Prussians are occupiers of Poland,’ she said, reminded of Maman’s habit of wincing theatrically whenever Prussia was mentioned. ‘My family is only here because the Prussians sit atop our rightful lands like a plague. While I would not wish harm upon yourself or the fighting men of my adopted homeland, you must understand I feel a great deal of hope when I hear that Napoleon is knocking at our door bringing with him the chance for an independent Poland within his Empire.’

The words had come out in a nervous rush, and she felt herself blushing, in part because she had got carried away and in part because she knew that so much of what she said was not her thoughts or feelings but those of her father.

So you’re parroting Papa’s political speeches now, she scolded herself.

‘I say,’ the young man said, rather startled. ‘You’re not rooting for this Napoleon fellow, are you?’ He was squinting suspiciously at her as if she were hiding state secrets beneath her petticoats and he could suss them out by staring at her bodice hard enough.

She blushed again. Fix this you silly thing, her inner voice snapped.

When he met her eyes and she laughed self-consciously, he was clearly a little unsure of himself, but Vera was pleased to see her good humour was carrying him along.

‘I am a mere spectator of this back and forth,’ she said aloud. ‘Britain has created its Empire abroad; Napoleon has created his in Europe. Neither Empire worries about what people fall beneath the boots of progress and expansion. I am on neither side in this; the French Republic may be as brutal as the Prussian tyranny in the end. I may never get to see the land of my forebears. So, I will continue to drink my tea and observe, while brave men like you go forth to decide the outcome of history. Are you not at all afraid to go?’

Bestowed by her words with the power to shape continents, the boy, whose name Vera suddenly realised she had forgotten, seemed to sit up a little straighter. It felt almost like one of her father’s experiments; she had tried a new track and got a better result. She felt a little more confidence, glad she had not upset the young man.

‘Well, of course,’ he said, attempting to put an authoritative tone in his voice. ‘Nerves are part of the soldier’s life. It’s dangerous work after all, but compared to the thrill of the adventure of it, the joy of doing my duty – why, I feel lucky to be sent!’

He looked so much like a schoolboy pleased to have been picked to play cricket for his school, that Vera was forced to lift the over delicate china teacup to her lip and hide her smile behind the hand-painted china.

He is sweet, so keen. She wondered if her own uncertainties showed as clearly on her face.

The tea was a late picking and tasted bitter, even with the rich creamy milk which had come fresh that morning from the Ladislaw’s herd. Vera was making a mental note to tell Mishka to spend a little extra on a decent blend when a new game occurred to her.

What fun that might be, she thought.

Waiting for the boy’s eulogy of the military life to come to a close, she took a small breath to steady her nerves and asked: ‘Are you very good at shooting a musket?’

‘Of course, the British army trains with live ammunition. No one shoots straighter or faster than a Red Coat.’ He may have actually winked at this point.

Vera was unable to precisely tell, although she found the ease with which his ego could be aroused or stimulated, rather disconcerting. It was an aspect of his nature that she was struggling to understand.

‘Perhaps, you could teach me to shoot after this tea if you are not to be called away to the frontline before dinner time.’

‘To shoot? That hardly seems something for a woman in your place–’

‘Quite right!’ called a voice from the large armchair by the fire. Its back was turned to give them privacy while Maman pulled her needle through some appalling dull embroidery of a rural scene.

Rightly concerned that the two young people be the subject of scandal, much had been made of ensuring Maman’s presence during their meeting. On the other hand, the need to give the potential lovers some privacy had also been considered. After all, two strangers coming to understand one another was a delicate process. So Maman had also made much of having the high backed armchair turned away from them so that she and her embroidery were wholly hidden from the scene, without risking any chance of scandal and, Vera suspected, to allow Maman to contribute as needed to the conversation.’

‘Nonsense, Maman. Father said he would teach me to shoot in time to go grousing with him. And to help him keep the crows away from the chicken coop. Surely, it wouldn’t hurt to have a military man’s opinion on my use of deadly ordinance.’

‘Your father is a fool. He treats you like a son sometimes, Vera. Can you imagine what Grandmamma would say to see the fruit of her loins learning to kill animals? Why she’d call you a poacher and fling you from the bosom. A daughter of mine, learning to hunt grouse before she has gotten to grips with the pianoforte or the French language. Never!’

‘My French is plus bon, ma mere.’ Vera laughed, turning to the young man, whose name she had forgotten. ‘Come now, Lieutenant. If you agree to teach me to shoot, as our guest, it will be unconscionably rude of Maman to reprimand you.’

‘Young man,’ began her mother in a voice that made the poor boy suddenly cower as if caught stealing by his own parent. ‘You will not–’

‘Of course, he will.’ Papa leaned out from a similar armchair on the far side of the room where he had been passing his time as a chaperone by napping over the financial pages. ‘He will save me the trouble, and should young Vera do something foolish, it shall be him at the wrong end of her blunderbuss and not I. I thank you, young man, for taking the education of my daughter into your eminent hands. I will, of course, join you in the garden to ensure that you are shooting only at the crows and not at my prize beef in the field next door.’

The drawing room in which they were sat opened into the garden through two large doors in the French style. It was a glorious English summer day, and the warm sun was perfectly countered by a soft breeze which drew the earthy smell of the cattle off the fields. Vera considered it highly romantic.

With some pride, Papa fetched his hunting musket, a beautiful German forged weapon nearly thirty-years old but meticulously kept. It had a fresh flint on it, and the wood was polished to a high sheen. The bronze casting on the butt showed two rabbits being chased by a lolloping hound, and it shone in the sun as Vera took hold of it.

Pulling a terribly serious face, Vera stood with the gun to her shoulder doing her best to look like the troops she’d seen marching through town. She laughed a little, and then caught the lieutenant’s eye.

‘You mustn’t mock my profession; you will upset me.’

He said it with a smile, but Vera could sense some genuine hurt in the cast of his gaze. Taking pity, she replied, ‘It will only be a mockery if I do not get it right. Show me.’

Smiling a little at her and with a tentative touch that betrayed his shyness, he took the musket and pushed it against her shoulders. ‘This is “attention”,’ he said. ‘When the command is to load, you move it like this.’ He guided the musket so the butt rested on her hip.

‘Then you prime the lock. He pinched off the paper hunting cartridge and let a little powder into the lock. Vera watched his hands moving dexterously, he seemed more confident in these little drill-square movements than he had seemed all afternoon at the tea table.

With a look of relaxed concentration on his face, she could appreciate the fine lineaments of his features.

As he showed her how to pour the powder, followed by the wadding, she found that she was getting a different kind of nervous, a gentle fluttering in her stomach.

‘The final step,’ he said, ‘is to slide in the ball and to add these four or five smaller buck shots, then we tamp it all down with the ramrod.’

Then he had her lift the musket to her shoulder, placing one hand on each of her shoulders and adjusting her stance. His hands were hot through the cloth of her dress, and she thrilled a little when he gently set them on her waist to straighten out her hips.

She felt the blush return to her cheeks and concentrated very hard on aiming.

Over the barrel of the musket, she could see the great oak they had chosen as a target. The gun was heavy on her forward hand and pressed uncomfortably into the shoulder of her dress. Under its weight, she could feel her hands shaking with the effort of keeping the cast iron barrel pointed at the tree.

The light glinted off the polished pan making the oak seem an impossibly small target, where a moment ago it had seemed childishly easy to hit and really very close indeed.

‘It will be loud,’ the lieutenant warned.

‘Don’t mind me,’ said Papa. ‘I am deaf in this ear.’

Vera’s arms strained as she closed her eyes and pulled the trigger.

In the darkness, there was a blood red flash which cast the thread-like pattern of her veins as shadows on the screen of her closed eyelids. There was a deafening bang that echoed immediately off the house behind her and again a split-second later from the hillside.

Then, from down the bottom of the garden, came an appalling scream of: ‘Murder!’

Vera opened her eyes in confusion and was immediately aware that she had missed the tree. The dark oaken bark was unscathed by her shot.

Instead, a brass fountain of Cupid further down the garden appeared to have taken most of the lead. The childish face of the statue had been almost entirely removed by the musket ball, and his chest and bow had been peppered with the buckshot.

It was just as well that Cupid had been placed where he had because beyond his shattered visage, Mrs Miniver – who it would appear had chosen that moment to visit the Ladislaw residence – had lost a good deal of the currant cake she was carrying to a stray round of buck.

Looking at the state of the small bronze statue, Vera dreaded to think what might have happened if he had not taken the bullets which she had accidentally fired right at Mrs Miniver.

And yet with the accident shown to have hurt no one, and only a few crumbs of cake to cry over, the sudden terror that had filled Vera’s consciousness receded, and in sheer relief, she began to laugh.

Mrs Miniver’s frightened face looked on in horror at what Vera was increasingly aware must appear a form of hysteria, but somehow this made her laugh harder.

Quite unable to help herself, Vera almost dropped the musket, which the lieutenant had to wrestle from her grasp to keep her from damaging it against a pot plant.

‘Could have killed me; the girl’s gone mad,’ spluttered Mrs Miniver. ‘Quite mad. Could have killed me. She’s quite mad–’ and so on, repeating her two key points to Mr Ladislaw who bowed over her and attempted to get her to drink some of the brandy which he, by order of Doctor Severn, had begun to drink throughout the day as a panacea for his nerves.

Perhaps she’s right, thought Vera who was quite unable to stop and explain herself apart from gasping out ‘I am so sorry,’ between the shuddering laughter which pressed out painfully against her corsets.

Mrs Miniver looked at her through a pair of thoroughly disordered spectacles, the old woman’s grey hair was pulling free of its pins and several long vines of grey were wafting around her face. She looked terribly old and frail, and suddenly Vera’s laughter stopped.

‘Quite mad,’ said the stunned Mrs Miniver.

‘You are absolutely right,’ said Vera, still catching her breath. ‘I am so awfully sorry. I was aiming for the tree, but I am so terribly clumsy. I put you in the most terrible danger.’

She felt tears welling up in her own eyes to match Mrs Miniver’s.

Now it was Mrs Miniver’s turn to look guilty, reflecting Vera’s own feeling back at her. Vera felt much better that they were perhaps growing a little closer over her foolishness.

‘You are quite right, Mrs Miniver. I must have been quite out of my mind to want to learn to do something so beastly as shooting, for the only people who shoot are those looking to kill someone or something. And murder, said Moses, is a crime.’

Vera was a little surprised by how quickly her feelings on this matter had changed, and she began to wonder if in fact her desire to shoot was another of her father’s ideas that she was parroting.

She scowled at the lieutenant whose face flushed red at first in embarrassment, then in anger.

He opened his mouth to speak, but Vera held up her hand and said, ‘No. That is quite enough. From now on, I will be a pacifist, supporting the total disarmament of all nations and a return to the vegetarian diet of Eden.’

I sound ridiculous, thought Vera, but her mouth seemed to be operating on its own as if the fear of having killed someone had cut it off from her.

Mrs Miniver was beginning to look worried. She looked up at Mr Ladislaw whose garden chair she had been carefully guided to sit in, and asked, ‘Is she quite alright?’

‘Oh, you know Vera,’ he said, his voice far more relaxed than his furrowed brow. ‘She is as alright as any of the women in the Ladislaw line. Warriors all, but as a result most dangerous in peacetime.’

Vera flashed anger. This is all his fault. Even as she thought it, she realised it was an embarrassed girl’s foolish attempt to regain dignity, but still her mouth went on without her: ‘Don’t speak of me as if I am not here, Father.’

Something about the situation had made her nerves decidedly mobile.

Is this what hysteria feels like?

She found herself jumping from one feeling to the next and trying to keep up with it. Something was stopping her from looking at the lieutenant whom she felt sure would have no desire to marry her at all after this.

Her father was mocking her in front of a man who he had picked out as a possible husband. She had been set upon by both parental disparagement and a kind of horse-trader’s empty promotion of his stock.

The embarrassment reached a peak, and unsure exactly why she was so flustered and angry, she turned and marched back to the house leaving Mrs Miniver to speak with her father.

Behind her, she could hear the lieutenant break into a half-run to keep up with her, with the unloaded musket still in his hands.

He really is quiet sweet, even after that scene, she thought.

‘She’s quite hysterical,’ was the last thing Vera heard from Mrs Miniver before slamming the door behind her.

Miniver sounded very close to hysterical herself.

Chapter 2

Vera recovered quickly from her irritation with her father and found herself fonder of the lieutenant for his gentlemanly way of dealing with her foolish outburst.

He really is quite sweet, she thought of him as she sat the next evening in her father’s study while they spoke about Mrs Miniver’s visit. The study was a small room with shelves piled up with his zoological samples in jars of murky yellow formaldehyde.

The room just about accommodated the writing desk in which Vera rummaged around arranging writing materials for a letter she was attempting to draft.

Her father sat in the over-large armchair which further filled up the room and made getting to the bookshelves beyond it difficult. The window over the desk was open to keep the room from getting musty, and a cooling breeze was wafting through the deep orange beams of light that fell on the desk from the setting sun.

Vera looked at her father who was only half-reading the book in his lap, his brow furrowed with concern as he thought of something then clearing as he turned to speak to Vera.

Though she hated to be mocked by him in front of other people, in private his gentle jibes seemed affectionate and teasing rather than mean-spirited.

‘Poor old Mrs Miniver,’ he said, chuckling to himself. ‘She only wanted to drop by to let us know that the Forsythe girl is getting married to the Millers’ son. Naturally, she doesn’t approve and wondered if I could have a word with the priest, that he might have a word with the parents, who might have a word with the conjugal parties and call the whole thing off.’

Papa’s chuckle had turned to that slightly mocking smile which Vera knew so well. He would smile like that whenever amused by the world around him; he never meant anything by it, but Vera always hated to be laughed at.

He seemed to Vera to want deep down to be a severe and serious person but was never very good at it; his good nature would always spill out, washing away any chance that he might rule his household with an iron fist as his father had.

She watched his smile and felt very lucky to have been raised by a man who took her seriously. Mama never did, always wanting to marry her off as if she were a coin to be traded for something more practical.

‘She is a terrible busybody,’ Vera said, unable to avoid sounding more apologetic than insulting. ‘It’s only on account of her still hoping for Benjamin Miller for her Sally.’

‘Perhaps it would have been better if you had missed that poor Cupid’s statue and assisted Miss Forsythe eliminating the major source of opposition to her match with young Benjamin.’

‘Oh, don’t speak of that, Papa. It was so mortifying. I really was very foolish.’

‘Everyone’s nerves were a little fraught after the accident with the musket, my dear. Mrs Miniver was very understanding of you. Though of course, she thinks me most eccentric for allowing you to wield a musket.’

Papa, she reflected, had a most uncanny way of knowing what was bothering her.

It is clever of him to know I feel worse for being hateful to him and the lieutenant than for the accident itself,

‘Speaking of the future Mrs Miller’s match, Father …’

‘Yes, of course, what did you think of the boy – I forget his name?’

‘That’s just it, Papa. I did too. He has the most forgettable of names. How could I marry a man of whom no one can remember the name? It is quite impossible, for his name would be mine, and what would I do if I kept forgetting that I am Mrs So-and-so of Whereverton. I would be made ridiculous. Still he was very sweet in his own way.’

‘Sweet he may be, my girl. But he seemed far too ready to be your accomplice in the attempted murder of an old busybody. Men should profess to be willing to murder for love, but they should never follow through. That is my opinion.’

He glanced up at the clock again.

He has been doing that all day, Vera observed to herself. So terribly on edge since a calling card had arrived earlier in the day. She was sure it had something to do with the strange men Maman had told her about.

She decided to seek an answer to the riddle: ‘Father, you are looking at the clock again. You’ve been doing this all evening. Are you expecting guests today? If so, at this time of night, the Mrs Minivers of this world will be asking all sorts of questions about such late night comings and goings.’

Her father chuckled in his way that suggested he was not going to take anything she said on the matter seriously. ‘I have some friends from the continent who wrote ahead to say they would arrive this evening. They will have travelled far.’

‘Are these the men who visited you last Saturday?’ said Vera. ‘You have been quite out of sorts since those visitors turned up. I do wish you would either get them gone from your company, or else find some way to reconcile. You do all shout so terribly.’

The terribleness or otherwise of the discussions of her father was hard for Vera to gauge. Although her mother had brought her up with excellent French and German, and a fluency in the language of the Old Country, Vera’s father’s numerous foreign associates discussed most of their issues in Latin, which as educated men was the one language they could all speak to some degree, and occasionally at moments of passion the men would burst into a flurry of words she could recognise as Russian punctuated by quotations and quite explicit diatribes in French. As a result, this mélange of languages was only understandable to her in its least informative moments; most of the discussion was simply Greek to her.

Her father’s foul mood had begun after a particularly agitated meeting held not in the study but out in the old barn, which had been converted by a lumbering crew of navvies into a printing press to reproduce pamphlets explaining the importance of a unified Poland to those Members of the British Parliament to whom the issue had not come up. In short, all of them.

Vera found this political foible of his amusing, but when his meetings with other agitators upset him, she became worried about his failing health. Already Doctor Severn had been by twice to deal with palpitations of the heart or some such trouble, and the attacks seemed to grow more serious each time they came.

Vera saw in every raised voice or impassioned speech, the spectre of a heart attack, and so she sought very carefully to follow the advice of Doctor Severn, taking down notes during every visitation and referring to them whenever her father’s behaviour seemed to run counter to his best interests.

The visitors who did speak in English were mostly of common stock. Sporting workman’s weeds and the type of flat cap and field boots which were common among the Somerset peasantry. Their jackets showed frayed seams on the collar and were made of a rough cloth. They came to speak about forming unions of land-workers or petitioning parliament for control of rents and adding tariffs on foreign corn.

However, it was the foreigners who took up most of Papa’s time. The small group of political movers who seemed to be headed up by an elegantly dressed man in a black tasselled greatcoat. Simple, military cut, in an old European style. On his shoulders were faded gold epaulettes from which hung two scarlet knots.

Atop his head was a well-worn silk top hat that appeared almost as old as its owner – an owner old enough that from beneath the top hat curved two magnificent, perfectly white sideburns which were long enough to seem to merge with his high-collar and silk cravat.

After his first visit almost a year ago, Mama had sought Vera out in the little window seat she favoured for a reading spot.

She was reading the ominous descriptions from Frankenstein that she would look back on with a sense of foreboding in the months that followed:

It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils. With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet. It was already one in the morning; the rain pattered dismally against the panes, and my candle was nearly burnt out, when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.

‘Did you see the coach they pulled up in?’ asked Mama.

‘No,’ said Vera.

‘It was quite remarkable. It looked like the kind of carriages from my youth, the long-distance ones. I thought for a moment I was in one of your novels about highwaymen or roving Jacobites.’

‘And what ludicrous plumage it was decked up in. Some sort of silk or cloth hanging coming off every bridle, bit, and strap on the horses and a coachman in a powdered wig. Why he looked like my grandfather used to when he attended a funeral.’

Vera had yet to see the men herself. In all the past year of their visits, they would arrive late at odd hours. This unusual funereal friend – if that was the word – of her father’s, was something of a night owl.

She would see the grooves of the heavy coach carved into the courtyard gravel in the morning. Occasionally, there would be one of the black feathers from the coach’s paraphernalia. On still nights, or when the wind blew across from the barn which Papa had converted to a printing press, she could hear the familiar tones of the man in the silk top hat speaking Latin with her father.

But something had changed on the previous Saturday; he had sweated more, paced more, and seemed to watch the clock like a man awaiting his execution.

Today though, she felt she had more pressing work to do than to worry about father’s heart. It was the lieutenant’s that was on her mind now. Having made such a mess of his recent visit, she felt it incumbent on her to fix her mistake. So she set about writing him a letter apologising and requesting a further meeting.

Perhaps she could amend the rift caused by her foolishness with the musket, which had quite ruined that afternoon.

It took her several drafts to get the letter to say what she felt. Or at least what she had convinced herself that she should feel. It would not be easy to marry a man she did not love, but for the family, for the trouble they were in, for that she would do anything, anything at all. She hoped to see her father smile easily and her mother cease her hand-wringing.

The words were set down with great care. It was important to give neither too much hope, nor to signal outright rejection. For the poor lieutenant had, after all, been so kind to her that afternoon, listened to all those little stories she told, and taught her to shoot. Even if he had almost assisted in the manslaughter of poor Mrs Miniver.

The inkwell into which she dipped the pen was a pretty little novelty blown in the shape of a boat’s hull so that the ink formed a sort of waterline around its waist and the pen when dipped formed a mast without the sails.

Her grandfather had used it as a reminder of how he had scrimped and worked buying by the boatload and selling by the cartload (with a modest increase in price to pay for his time, of course), and in time, he turned his small percentage cut into enough to buy his own boats and carts. Eventually using his capital to put down roots into English soil when he bought this small run-down farm.

On the table beside the letter were sketches her father had drawn, in his highly detailed style, of the first cottage he was planning to build on one corner of the land.

The hope was that eventually the farm would be handed over entirely to tenant farmers who would pay their rent to Papa in retirement.

The landed equivalent of grandfather’s buying by the boatload, selling by the cartload, thought Vera.

She turned back to the letter she was writing. Its three old drafts sat in a pile covered in blots and with large paragraphs struck through and rewritten. To pour out a heart’s worth of emotions from a heart that felt nothing was near impossible.

Her father continued to read quietly in the armchair to her back, answering questions on the composition of the letter as she asked them.

The sun had warmed the room, distorted into the many colours of the rainbow in places by the uneven thickness of the glass. It was marvellous, wasn’t it? she pondered. That one man could blow glass so delicately as to make it a bottle shaped like a boat, while another had only to make a sheet but could barely make that even.

How many types of person are there? And where is the one for me? What would Charity Forsythe write to Benjamin Miller?

Yes, that is the way to do it.

She would cast her mind into the pool of another’s feelings. Just as writers must do when they write up their romances.

She glanced over at her father’s bookshelves, the heavy printed tomes of which he read. The titles were in a half dozen languages; the ones she could read were all scientific. He was entranced by the discovery of the world, by the great Romantic sweep of history.

When she was younger, he would sit her on his lap and explain the diagrams of shapes and objects that existed only in the mind of mathematicians or far above them, visible only down a telescope far more powerful than the microscope he used to draw his own diagrams of the differences between the ticks that infested his cattle and his sheep.

Her own books told her stories closer to her heart. Of marriages for love, a prospect that even as she tried to create it in the letter, seemed so truthful and believable on the page but alien and unimaginable for her in real life.

Did Mama get to marry for love? Of course not, yet she is quite happy with Papa. So it shall be with me and –

But his name remained forgotten so she wrote – “My Dearest Lieutenant …” at the top of yet another clean page, brought the blotter down on it, and rolled the soft paper over the words which shone a little, still wet but with beautifully clean edges.

Once she had finished, she read the letter through, and finally, four drafts in, There was too much to do, and she wanted to call on a few school friends in town before it got too dark.

Leaving her scribblings beside the image of a future cottage, she set about finding her favourite bonnet, the dark grey one with a bright white ribbon. Such work to keep clean, but such a pretty result.

In the end, she couldn’t find it and made her way into town with her second favourite cap which her mother had chosen for a Christmas present.

Chapter 3

The visitors in the plumed coach did not come that evening. Father said something kept them away; instead, they visited again a few weeks later, and this time Vera saw them.

She didn’t know they were coming until she saw the old-fashioned carriage pull up near where she was pumping water with Mishka in the shadow of one of the barns that made up three of the walls of the farm’s courtyard. The fourth wall was made by the back of the farmhouse itself, with its small garden on the other side and acres of cattle grazing all this side of the main road which ran to Bathcombe.

The coach was large enough to be mistaken for a public stage and was drawn by four horses which wore long black feathers hanging in long rows from their tackle – just as mother had described.

Even the blinders and the bits in the horses’ mouths dripped plumes in the same crepuscular colours, black and grey. It gave the impression that these were not horses but some sort of feathered steed from out of Greek mythology.

The effect was to make the stage appear both celebratory – such was the excess of decoration – and also as if it were in mourning, so complete was the blackness of the colour scheme.

‘It’s terribly morbid,’ Vera suggested to Mishka.

‘I do not like it either, Miss,’ answered Mishka, barely looking up. ‘It doesn’t please me at all. With those feathers, I think it might fly away.’

‘You know I can just imagine that.’ Vera laughed. ‘Yes, like a demonic mirror image to Ezekiel’s burning chariot.’

‘Shhh, now, Miss. Don’t go invoking the Bible in vain. You’ll set trouble on us.’ Mishka said this with perfect earnestness. Vera was careful not to laugh at the maid’s superstition. She knew that Mishka would spend some of her wages each month to consult a professed wizard who lived as a hermit in the nearby woods, and the servant put great stock in the appearance of black roosters and stillborn cattle.

From the carriage stepped two men, who Vera watched as Mishka continued to work the water pump. The man with the white sideburns was the first out. He wore the same shabby top hat and greatcoat that mother had described.

He had a serious limp but refused the walking stick offered him by his companion. He looked tired, brow furrowed beneath deep and concerning thought. Neither of the men seemed to spot the women working in the corner of the square, so Vera could take the time to study these men closely.

On inspection, the gentrified air of the man fell away. The uncombed sideburns thrust in all directions as if ruffled by a gale. Tufts of his hair seemed to have pulled free and stuck to the rim of the hat in scattered places.

His single associate was well over six feet tall with a face that was divided into a haphazard patchwork by dozens of bright white scars which stood out against his dark, sun and coal browned skin.

Vera had the cold iron handle of the water pump in one hand and the slowly filling wooden bucket in her other. On seeing her father rushing out to meet the men and usher them into the printing barn, she set the bucket down and left Mishka to finish the task.

‘Don’t you go snooping,’ was Mishka’s whispered suggestion.

But where’s the fun in that?, thought Vera, slipping away.

Treading carefully on the crunchy gravel of the courtyard, Vera slipped in to approach the hay barn which allowed her to avoid the line of sight from the print room’s windows as she made her way around the edge of the square.

Her heart beat heavily in her throat as she took in the warm, rich smell of the drying grass. How lovely it would be to lie down among the bundles.

Then a rat stirred scuttling from one hayrick to the next in the gloom of the barn; it reminded her that soft as it looked, the hay piles would be thick with vermin. She changed her mind about lying down.

The door that opened up by the print shop’s southern wall was heavy and gave only with the greatest reluctance, as if something on the other side were pushing back at her trying to keep her from completing her investigations.

She had to be careful while forcing it, not to make a sound with the squeaking hinges. While the scraping of the hinges might alert the visitors, Vera was far more worried about the effect of her inquisitive behaviour on her father’s good opinion of her.

His warnings about the visitors echoed in her ears. But rather than driving her away from the heavy door and back to the pump, the warnings seemed to pull her forward to the door.

The handle transmitted the warmth from outside to her hand as she struggled with it one more time, hearing the scrape and click of the catch, and then with infinite patience, she slowly drew the door open.

She wore a simple empire waist dress, in an unobtrusive grey, perfect for easy and quiet movement. She felt confident she could make it to the window without giving herself away through the unnecessary noise.

Her concerns were further allayed when she heard coming from the print barn the sound of raised voices, shouting across each other in a mix of Russian and Latin.

When she sidled up to the windows, she found her caution misplaced. The window was shut from the inside, the glassless windows of the printing barn stoppered up by hefty wooden shutters. No one inside would have been able to see her approach even if she had brazenly walked right up to them.

Suddenly, her blood ran cold. For a moment, she felt sure she must have misheard what her father said. It was not just the word though that sent the chill rushing through her veins and raised her hackles right down her spine. It was the tone of the word, the desperate pleading in his voice.

Then he repeated it, and she was running towards the door of the print shop.

‘Please,’ he had screamed. ‘Please don’t.’

She threw the door open and saw her father kneeling in the rushes that covered the floor of the building to absorb any spilt ink. The scarred man had a flintlock pistol pressed to Papa’s head while the man in the top hat had his back to the whole scene, hands clasped behind him with the air of an admiral on his flagship’s deck.

She tried to scream, but like in a dream she found her throat dry and stopped. The tall man was looking to the eminent white-haired gent, who with a casual wave of the hand seemed to indicate something to his lackey.

There was a roaring detonation.

Vera didn’t see the shot fired; realising what was happening, just before the puff of smoke, she turned away and fled.

I am too late, she thought gasping for breath. Panic gripped her. The fate of her father had been sealed, and she would live with the awful aftermath of his loss for the rest of her life. But right now, the need for self-preservation overwhelmed everything.

So she ran, and as she ran, Vera heard her mistake in the deafening footsteps on the gravel. They would know there was a witness. Still, she ran on, across the courtyard, past the coach to the back door of the main house. Her voice would still not comply; she could raise no scream, no cry for help she wanted.

She did not dare to turn to look back but could hear the boots of the two men crushing the gravel in her wake. Mishka stood by the pump, looking towards the print room then to Vera, then back to the print room.

‘Misha run, run!’ Vera finally found the breath to shout. But her voice was hoarse in her throat. She must think this is some kind of game was Vera’s only thought before she threw the latch on the front door and ran inside.

The cool gloom of the hallway took a moment to adjust to after the bright light outdoors. And her brief blindness gave her a moment to return to her mind. Through the mist of abject fear and grief, she remembered the movements the lieutenant had taught her. To prime the chamber, to pour the powder, to ram home the balls.

She rehearsed these movements in her head as she rushed through the house, up the stairs to her father’s gun cabinet in the warm smoky confines of his den.

She saw her drafted letters still neatly placed at the side of the desk, everything still in its place. As if nothing had happened.

I was too late, still circled in her mind. But what could she have done? Alternatives rushed through her head.

There would be time for self-recrimination later.

So small was the room, and so packed with natural history samples, jars of pickled amphibians and rows of stuffed rodents, that she had to squeeze between the chair and the wall to get at the gun cabinet.

With shaking hands, she primed the musket and poured the powder.

From elsewhere in the house there came another shot.

Mama? No. I should have found her, warned her. Stupid girl, Father may have been dead, but you could have warned the others.

A small voice, barely audible responded in her head. You panicked. Don’t think about what could have been done. What is next?

The answer she thought must be to prime the chamber, pour the powder, and ram home the balls.

She hoped Mishka had the sense to have hidden after hearing the shot and seeing Vera’s fear.

She was doing everything wrong, making everything worse. Why hadn’t she peeked sooner, intervened when she saw the gun, warned Mishka.

The ball and buckshot rattled down the barrel. The rod scraped, and then she was standing, unsure of herself with an inheritance from her father in her hand that was designed for one reason: to take life.

The stairs outside were creaking as someone came up them fast, but quietly. She cocked the flint.

The steps came closer. She heard the banging of doors swung open further down the corridor.

They were looking in her room, then her parents. The footsteps came closer. The two men were whispering to each other.

She pointed the musket at the door.

So close to the door, she wouldn’t even have to aim really, not like with the tree in the garden.

Then she remembered the look of fear on Mrs Miniver’s face. Remembered her own panic as she ran across the square back to the house.

Thou shalt not kill, she thought. Could hear the words in the Reverend Thatcher’s voice. The next door banged open, an empty cupboard. Then the feet were outside the study door.

The handle turned, and in one movement, she ducked behind the massive chair and clicked the flint shut over the pan. The door slammed against the shelf behind it, smashing a foul-smelling jar of formaldehyde in which a jellied monster had been carefully preserved.

The smell tickled her nose, and Vera wanted to sneeze. She fought it, so close to her pursuer that she could hear him breathing. Her own breath was stopped; she let a mere hint of breath out and in, scared that to take a full breath would rustle her dress and give her away.

In the cramped space of the room, the hulking brute of a man was limited in his movements. He glanced around then moved off along the corridor, and moments later, she heard him clattering about in the guest bedroom.

She slipped out from behind the chair and listened closely at the door. The men were speaking to each other in angry voices at the far end of the corridor. Vera had a chance to shoot. She raised the gun, but her hands were trembling so violently that had she shot, she would have struck the wall, and they would have killed her in an instant.

Dare I run?, she wondered, feeling as if she were no longer inside herself but looking down on a small version of Vera in a dollhouse of the lodge. As if she were some sort of guiding angel there to assist herself through this trouble.

But in her safe and distant viewpoint overlooking the little doll of herself, all those troubles seemed to her to be nothing more than the stories she told herself as a girl about the goings on of her cloth dolls or the little wooden and tin animals.

The voices at the end of the corridor became fainter; they were going down the back stairs towards the servant’s quarters. Mishka! thought Vera. If she had slipped away, she would have almost certainly hidden away in her rooms to wait out the trouble. She wished she knew where Maman was.

Although the house had rooms for a full complement of servants, the Ladislaws in their current state of relative penury could only afford to keep Mishka, another Polish émigré to assist Maman with her work.

She had to do something to rescue the poor woman, for these men would surely commit murder and rapine on any poor women they found in this house.

Sliding the door open she pointed the musket down the empty corridor and pulled the trigger. In the enclosed space of the room, the report was deafening, a caustic stinging smoke pricked her eyes and stung her nostrils, and she staggered backwards from the kick of the gunpowder. The window at the end of the corridor exploded outwards into the garden.

‘Run,’ she screamed. ‘Mama, Mishka, run! They have killed Papa. Killed him dead. Murder, murder, murder.’ She hoped that it would be enough to get the others out and about.

She had not realised she was running again, hitching her skirt up and hurling herself down the stairs. Footsteps were hammering across the hallway above her, back from the servants’ rooms as she plunged away from the stairs then through the airy space of the drawing room and out into the garden.

She was still gasping out the word ‘murder’ over and over even as she cleared the garden gate and, staying low like a fox giving slip to the hounds, rushed along below the garden wall and passed over the style at the end of the road and into the long grass of a field in fallow.

If she could make it to town by evening, she could find a constable or night watchman and bring to their attention this horrific crime.

She trudged across the fields, avoiding the road for the first few miles. Then Vera saw the remarkable coach overtake her speeding its way towards town. She caught sight of the two men aboard it, and as her panic subsided, worry and guilt began to forge upward from the depths of her mind. She retraced her steps back to the house. With palpating heart she opened the door, the smell of smoke of gunshot still heavy in the air. The parlour door was open, and there spread-eagled across the floor lay the body of her mother. No breathing, no pulse. Tears choked up inside her until, summoning the remnants of her courage, she trudged upstairs to be met with a scene all too similar – Mishka, dead on the floor.

It was then that Vera turned and fled with heavy heart. She had to get to town, get help to apprehend the evil men who’d done this to her parents, to Mishka.

After two hours of walking, with Bathcombe showing sprawled across the hillsides whenever she topped a rise, her feet were beginning to hurt, and she could feel that her heel had worn a hole in her right stocking. The hem of her dress was caked with dust that seemed to weigh the cloth down as if it were water.

This pain of the body was a relief to her mind, though, a mind wracked by a more insidious pain. Father dead, and Mother, and Mishka.

She would get revenge for their horrific murders. She would find the constables and ensure justice for her family and Mishka.

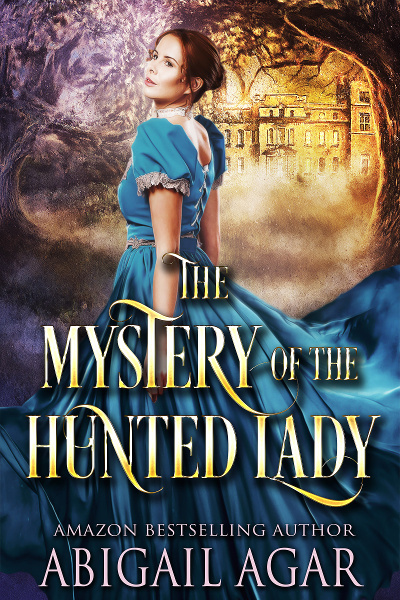

“The Mystery of the Hunted Lady” is an Amazon Best-Selling novel, check it out here!

Vera Ladislaw, a third generation Polish aristocrat, lives a quiet life in England, with her father dabbling in political reform and agricultural innovations, and her mother always on the hunt for a good husband. When the unthinkable happens, Vera’s life is torn apart. Alone, framed for a terrible crime and on the run, she disguises herself as a boy and finds work at the remote and storied Avonside Manse, where a mysterious Lord lives in splendid isolation. Will she be able to discover the truth?

Lord James Stanley, despite his extravagant balls and his rakish ways, is a rather lonely figure. When he finds a confidant in the alter ego of young Vera, a strong bonding is to come. He keeps well-sealed secrets himself, but when Vera’s true identity is revealed, will he still stand for her innocence? Will he be able to trust her?

Despite him being a notorious libertine, Vera finds there is more to him than meets the eye and soon finds herself caught in a complicated web of romance, intrigue, and danger. How will they manage to untangle this web and find true happiness in one another?

“The Mystery of the Hunted Lady” is a historical romance novel of approximately 80,000 words. No cheating, no cliffhangers, and a guaranteed happily ever after.

OFFER: A BRAND NEW SERIES AND 2 FREEBIES FOR YOU!

Grab my new series, "Love and Secrets of the Ton", and get 2 FREE novels as a gift! Have a look here!

Hi there, dear readers. I hope you enjoyed this preview! I will be waiting for your comments here. Thank you 🙂

I am ready for the book.I want to know how Vera gets the two who murder her family members.Looking forward to the launch date.

So glad to hear that, my dear Thelma!

Looking forward to reading.

Glad to hear that, my dear Barbara!

It was very suspenseful! Hoping to read more about what happens to Vera and who murdered her family.

You will know soon, my dear Wendy!

I am so look ing forward to read this book! I am not usually into mysteries, but I really need to know how it all unfolds!

Thank you:)

You’re welcome, my dear Latashia! Hope you’ll enjoy my book! Make sure to stay tuned 🙂

A very tantalising preview, I can hardly wait for the rest of the book to be published. I have to find out how she gets on.

Also I like the atmospheric cover.

Thank you very much, my dear Sandy! Make sure to stay tuned! Hope you’ll enjoy it!

I am looking forward to the rest of the story and to find out what happens.

So glad to hear that, my dear Beverly!

It sounds really wonderful can’t wait to read the whole book when it comes out

Thank you, my dear Maria! So glad to hear that 🙂

Oh ! Sounds absolutely thrilling . I also love the cover you chose.

Thank you so much, my dear Linda! Hope you’ll enjoy my story!

I am excited to find out what happens to Vera and who murdered her family.

You’ll figure out soon, my dear Sharon! Stay tuned!

I want to know WHY the men were involved with Vera’s father, when he seemed such a mild, ordinary man with a sense of humor. Something unusual I would think- providing an interest arousing question that one just has to find the answer by reading the book!

You will know soon, my dear Joy! Make sure to stay tuned!

I can’t wait to see how Vera clears her name.

You’ll figure out soon, my dear Marilynn!

I love a good mystery and a brave woman too. This book looks like it will meet both of my ideas of a good combinations of a good book. Add a little, or a lot of romance and intrigue into the mix and you will have me hooked untill the end of the book.. I cant wait for “The Mystery Of The Hunted Lady” to come out. I know it will be a good read as only Abigail Agar can write!..Shirley

Thank you so much for your kind words, my dear Shirley! Hope you’ll enjoy it!

Can’t wait for the rest of the story.

So glad to hear that, my dear Renee!

Wow!! Talk about grabbing your interest and leaving you gasping. I so look forward to reading the rest of the story and finding out the “who done it’s” and what Vera’s father was really involved in. Of course there must be redemption and a happy ending too.

You will find out soon, my dear Kelly! Make sure to stay tuned 🙂